3D-Printed Boat Hits the Water

In October, Italian firm Moi Composites made a splash at the 2020 Genoa Boat Show by driving the world’s first 3D-printed GFRP boat into a nearby harbor. The MAMBO (Motor Additive Manufacturing Boat) is a 21.5-foot long speedboat constructed with parts made from glass fiber and vinyl ester resin.

The boat was inspired by the 1973 Arcidiavolo, an offshore racing boat designed by the father of modern speedboats, Sonny Levi. However, the MAMBO is anything but traditional with its deep undercuts and narrow geometries made possible by moldless, digital manufacturing. “You cannot manufacture this shape using traditional composite manufacturing technology,” says Gabriele Natale, CEO of Moi Composites.

Moi co-founders Natale, Michele Tonizzo and Marinella Levi began their work in 2015 at the +Lab additive manufacturing laboratory at the Polytechnic University of Milan. After reviewing existing 3D printing technologies, the team set out to develop a 3D printing process for thermoset composites. “In the beginning, additive manufacturing normally employed low-performance material, but we were convinced that in the future, additive manufacturing would start to produce with industrial-grade material,” says Natale.

Later that year, the researchers developed a now-patented continuous fiber manufacturing (CFM) process for glass and vinyl ester. After three years of honing the technology, they spun off Moi in 2018. The company initially produced small-scale prototypes of bicycle frames, prostheses, skateboards and furniture. Soon, however, they decided to demonstrate the scalability of their process by 3D printing the MAMBO for the Genoa Boat Show.

Natale says it was the perfect venue. “Every year, they present really new, cool concepts there,” he says. “But they are often hard to reproduce using traditional composite technology. That is why the MAMBO has this organic, really extreme shape. We printed it to demonstrate that by using a digital process you can push forward creativity and imagination.”

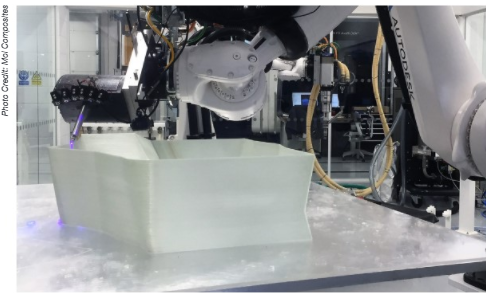

The MAMBO’s 50 GFRP parts were fabricated by pulling Owens Corning’s SE1200 single-end Type 30™ roving through a vinyl ester resin bath formulated in-house, then feeding the roving to a Kuka KR QUANTEC robot for placement. Moi printed half of the components in Milan, while Autodesk printed the other half in its advanced manufacturing facility in Hampshire, United Kingdom. The GFRP parts ranged from 20 inches in length for the tip of the boat to five feet for the beam. Each component was designed with a male and a female attachment that fit into those of adjacent parts to create a continuous, overlapping structure.

Once completed, the parts were joined and laminated at Catmarine shipyard in Lecce, Italy. The components were first glued together into seven sections. Each section was then laminated with GFRP fabrics, polyester resin and a PVC core using hand lay-up. The entire structure was then laminated again to create a one-piece sandwich structure without hull-deck division. No fasteners were used. After curing, the hull received a gel coat and the deck was painted a vibrant blue, metallic color.

“I think one of the biggest challenges we had was how to assemble the final structure,” says Natale. “That was really complicated. We had to imagine a way to join all the parts together and laminate all the sections together in a way that was strong enough to create a boat – a real boat – that was deployable in the sea.”

As of February 2021, MAMBO had logged approximately 100 hours on the water at speeds of up to 25 knots. Once coronavirus boating restrictions are lifted, Moi plans to move the MAMBO to Milan or Lake Como and use it regularly. In the meantime, the firm is already planning for MAMBO 2.0.

“We gained a lot of knowledge about this kind of boat construction, and already have some ideas that can improve the next version of the boat,” says Natale. For instance, the company has experimented with printing the sandwich structure directly using the robotic arm to save production time and maximize performance. Ultimately, Moi hopes to produce one-of-a-kind boats using mass customization. Allowing customers to create their own personal boat model will free up designers to push the design envelope.

“The creativity of many designers today is suppressed due to various factors – technological, geometric limits or production costs. And there are countless noteworthy projects destined to remain magnificent renderings forever,” says Natale. “However, with CFM technology these designs can become real.”

SUBSCRIBE TO CM MAGAZINE

Composites Manufacturing Magazine is the official publication of the American Composites Manufacturers Association. Subscribe to get a free annual subscription to Composites Manufacturing Magazine and receive composites industry insights you can’t get anywhere else.