It Takes an Industry to Attain Sustainability

Sustainability has become a watchword for businesses in the 2020s. Consumers want the companies they deal with to use sustainable practices, while governments are adopting policies holding corporations responsible for their products’ environmental impact from manufacturing through end of use.

The composites industry is responding to the changed marketplace. “For a long time, people were focused on all the great benefits that composites bring during their lifetime. There was not a great deal of attention focused on what you do with them at the end of life,” says Malcolm Forsyth, sustainability manager for Composites UK, a British trade association. Those benefits are no longer the only focus. “People are starting to ask a lot more questions about using recycled materials, particularly in Europe. … We need to start recovering and moving to a more circular life cycle model rather than a linear one.”

In the last few years, composite manufacturers and suppliers, universities, research institutes and organizations like ACMA, the European Composites Industry Association (EuCIA) and Composites UK have been working together to address these challenges.

Materials Matter

There are three phases in a composite’s life cycle: the making, the use and the end of use. Much of the emphasis today is on the last phase, particularly recycling.

“That is understandable, but it may overshadow the very positive effect of composites, especially in the use phase,” says Ben Drogt, founder of BiinC, which assists companies in developing innovative and sustainable solutions. “Composites are historically used because of their light weight and their high durability, providing a long life with minimal maintenance. Both are key elements for sustainable materials.” He notes that wind energy would not be possible at the current scale without composites, nor would the reduction of fuel usage in aircraft and land vehicles.

During the use phase, the durability of composites is a plus; a small composite bridge, for example, can be moved to another spot if it’s no longer needed in its original location. The problem comes when no one wants a 50-year-old fiberglass boat or when turbine blades reach end of use. Researchers are now exploring a variety of technologies for recycling and reusing these composites. One commercially feasible solution is to use composite waste as raw material in cement production, as is being done by Neowa GmbH and Holcim in Germany. In the U.S., the Rhode Island Fiberglass Vessel Recycling Program has been launched by Rhode Island Sea Grant and the Rhode Island Marine Trade Association to dismantle and reprocess FRP boat hulls into cement.

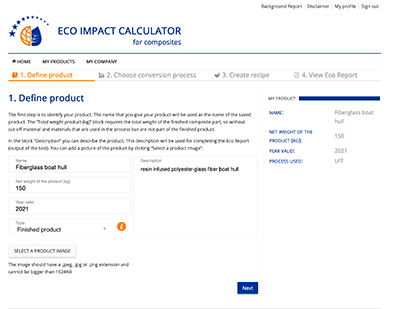

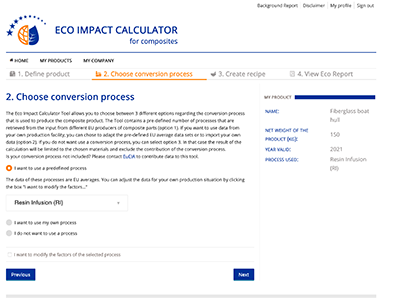

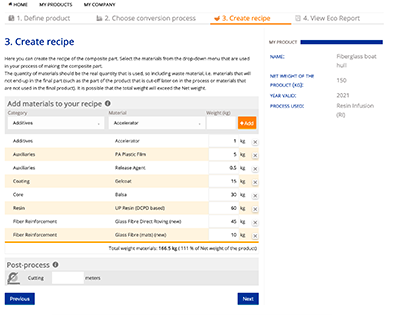

At the start of composites’ life cycle, manufacturers are finding more sustainable options, such as natural fibers and bio-based polymers. They can also choose lower energy production processes, like pultrusion instead of spray-up. When making their material and production selections, manufacturers should consider a product’s overall life cycle, but that’s difficult to do on their own. That’s why EuCIA, in conjunction with BiinC and EY Cleantech and Sustainability Services, has developed a unique tool that can guide their choices – the Eco Impact Calculator (ecocalculator.eucia.eu).

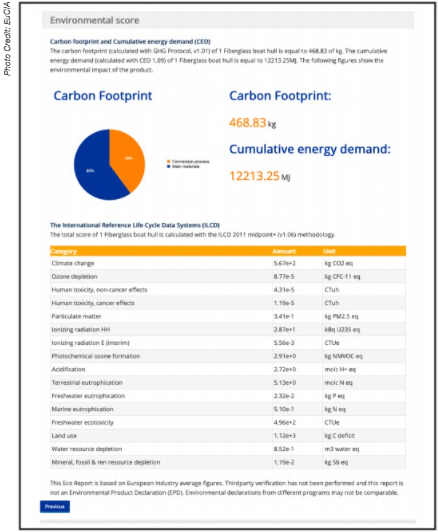

To get the life cycle assessment (LCA) of a particular product, companies enter information about their chosen materials and production method. The calculator will produce a report on a product’s carbon footprint and its impact on 16 areas, from climate change and ozone depletion to human toxicity and natural resource depletion. “By having the eco-footprint of a composite part calculated now, based on sound principles found in the background document for the Eco Calculator, one would be able to use the result as input for full life cycle calculations,” says Jaap Van Der Woude, chair of EuCIA’s sustainability committee.

Building the calculator was a years-long and very costly process. EuCIA’s sustainability committee worked with the German Composite Federation to pull the LCA information together. They obtained information from GlassFibre Europe, PlasticsEurope and a few manufacturers, plus production process information from European composite manufacturers. From this they developed the industry average data for the Eco Impact Calculator.

EuCIA launched the calculator in 2016 and has continued to update it with information about carbon fiber, thermoplastics and now natural fibers. The response has been good.

“The users of the Eco Impact Calculator now number in the thousands, and there are people from every continent using it,” Van Der Woude says. OEMs and other composite customers are encouraged to try it out as well. “When they are trying to decide whether to make a part of reinforced plastic or steel or aluminum, they will now have the ability to use reliable, average European data for composites [to make life cycle calculations]. It’s as good as it gets.”

Filling the Gaps

One thing became very clear during the creation of the Eco Impact Calculator: it’s going to take the collaboration of many companies and organizations to make the industry’s sustainability efforts successful.

Composites UK has brought together consortiums of interested parties, including composites companies, equipment manufacturers and parts producers, to help the industry develop a more circular life cycle for composite materials. Forsyth also works with other industries’ associations. Addressing end-of-use issues with turbine blades, for example, will take a concerted effort from blade producers, wind farm operators, waste managers and academic institutions.

“We’re also trying to get different market groups to think outside of their own markets, to make connections so there’s a cross-industry solution,” Forsyth says. What turbine blade recyclers learn could be useful to those trying to recycle GFRP boats. Cooperative efforts could also help create the scale the composites industry needs to make these efforts successful.

In 2016, the UK’s ReDisCoveR project, created by the National Composites Centre (NCC) and six other government-sponsored innovation organizations, brought together representatives from more than 100 companies and organizations, as well as researchers and customers to work on the problem. Their goal was to identify issues around end-of-life composites, especially gaps in the supply chain that prevented using more sustainable materials during composite manufacturing or recycling composite materials at their end of life.

“The gaps came down to logistics,” says Tim Young, head of sustainability at NCC. “It’s not that technically they can’t do it. There are logistical challenges and economic challenges that prohibit things from taking place, such as the cost of transporting material.” It’s difficult for composites manufacturers to repurpose their scrap fiber when it’s not economically feasible for them to transport it to a place where it could be processed into something new.

Last year, NCC and the Centre for Process Innovation (CPI) created the Sustainable Composites partnership. Its purpose is to accelerate the development of net-zero impact composites, processes and technologies. It brings together experts who can help move breakthroughs quickly from research into applications.

The most pressing issue today is composite waste from legacy products, Young says. The industry can’t just focus on high-value waste streams like carbon, and it can’t concentrate only on large, company-owned assets like wind blades. It also needs to address what happens to composite material commodities that individuals own.

The further use of biomaterials must also be explored. “We’re seeing all of these good things coming out from different research institutes, but we need to be working much closer and collaborating with them,” Young adds. There’s been some progress. Some major research institutes are already trying to align their programs so they produce a more immediate impact on the market.

It’s important that organizations share information to avoid duplicating efforts. That’s why the Sustainable Composites partnership will be working with EuCIA to understand the processes they used to build their Eco Impact Calculator, rather than starting fresh.

“We all have to do our part in the context of what’s happening globally,” Young adds. “What we’re seeing is an awful lot of people who are making bricks, and they’re all developing really good technologies and solutions and economic models and studies. But at some point, we have to put these bricks on top of each other and build a wall. We can’t just keep building bricks.”

Developing the Markets

A steady market for recycled fibers and resins and for biomaterials is essential to a more sustainable composites industry. Companies are beginning to recognize the opportunities.

The World Federation Sporting Goods Industry and McKinsey & Company have identified sustainability as one of eight trends that will shape the sporting goods industry in 2021. Encore, a manufacturer of high-quality wheels for racing and training bikes based in Milford, Mich., is doing its part by incorporating sustainable carbon fiber into its products.

Vartega, located in Golden, Colo., is supplying high-grade carbon fibers produced through a proprietary process from various dry fiber and prepreg scrap sources. “Vartega’s carbon fiber has the same mechanical properties as virgin carbon fiber, at a fraction of the cost,” says Andrew Maxey, Vartega’s CEO.

Encore uses computer-aided technology to design the wheels, then injection molds them using carbon-fiber reinforced nylon supplied by The Materials Group (TMG) of Rockford, Mich. Encore’s wheels are highly stable, aerodynamic and have excellent structural integrity, according to the company. The carbon fiber provides superior lateral stiffness, which makes the wheels very good at cornering and at transferring the maximum amount of power from the pedal to the ground.

The wheel has thin cross-sections which can be difficult to mold, but the material with the recycled fiber is doing the job. “We are filling thin areas with tricky knit lines and also maintaining a very nice finish,” says Ed Giroux, Encore’s founder. “Vartega has stepped up to the plate and offered a material that has fulfilled our requirements. TMG has offered the support that was necessary to accomplish this.”

Maxey says that Encore’s wheels are a great example of what’s possible when world-class design meets top-notch materials. “Sustainable carbon fiber sets a new bar for reinforced thermoplastics,” he says.

Smooth Sailing

Another example of setting new bars for sustainability is the Flax 27. The sailboat’s deep, clear finish showcases the sustainable materials used in its construction. The flax fibers in the boat’s composite structure and the cork decking give the Flax 27 a look akin to a wooden boat. The epoxy resin that provides the glossy finish contains 31% bioresins made from linseed oil. Although the sandwich layers between the composite shells aren’t visible, they are also sustainable, filled with material made from recycled plastic bottles.

Designed and built by GREENBOATS, the vessel represents a decade of biomaterials research by Friedrich Deimann, the company’s founder and managing director. When he first used composite materials as an apprentice boat maker, he was excited by their lighter weight and the freer form possibilities they provided. But he didn’t like working with the glass fibers and the resins.

Deimann began researching material alternatives in 2010 and built his first boat from biocomposites as his project to become a master boat builder. He founded GREENBOATS in 2013 to continue this work and introduced the Flax 27 in 2019.

Using biocomposites for the boat didn’t require sacrifices in the composite properties. The flax fibers have the same tensile strength as glass fiber but at half their weight. Most important from the sustainability standpoint, flax fibers require only 20% of the energy required to produce glass fiber and only 5% of the energy needed for carbon fibers.

GREENBOATS has expanded its portfolio of sustainable materials to include cellulose fiber and recycled carbon fiber and has produced a resin made with 88% biomaterials.

“When we’re developing something for a client, we always keep three main variables in mind. One is performance – stiffness, weight and so on. Another is cost. And the third is sustainability,” says Deimann. The work always includes a life cycle assessment. “We have a quantitative approach toward sustainability. We always try to measure the exact impact in terms of CO2 and input energy,” says Jan Paul Schirmer, who partners with Deimann at GREENBOATS.

Using biomaterials can add a 20% to 30% premium on a product’s initial cost. But Schirmer says GREENBOATS’ customers need to consider the operational expenses over a lifetime, including the cost of disposing of it when it reaches the end of its useful life. Recyclable biomaterials provide a real economic advantage at that point.

While GREENBOATS will continue to build boats, it is now pursuing other industries. “The idea is to create applications that give us more of an opportunity to standardize production and become cost competitive,” says Schirmer. Panels for transport vans are one possibility.

Sustainable 3D

The composites industry is continually developing biomaterials and new applications for them. Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) has partnered with the University of Maine’s Advanced Structures and Composites Center, home to the world’s largest 3D printer, to develop sustainable feedstock for large-scale composite printing comprised of bio-based resins and fillers.

The research team has been working with nanocellulose, composed of nanofibrils isolated from cellulosic material. Since Maine has a large forest products industry, the team primarily derives the cellulose from trees and wood pulp, but is also exploring other sources, such as plants, agricultural wastes and recycled cardboard. Cellulose nanomaterials are lightweight with a high tensile strength, low density and high thermal stability.

“As a forest product, cellulose nanomaterials could rival the properties of traditional metals and petroleum-based materials, and their successful incorporation into plastics shows great promise for a renewable feedstock suitable for additive manufacturing,” says Soydan Ozcan, senior R&D scientist and sustainable manufacturing thrust lead at ORNL. Researchers have already printed a 1,200-pound mold for a boat roof using a thermoplastic polymer (PLA) composite containing microcellulose and nanocellulose fibers. The team at ORNL and the University of Maine is also exploring other applications of large-area, bio-based composite printing in the marine, building/construction and packaging industries.

“We are working in the areas of cellulose production, material formulation and development, and manufacturing technologies in order to bring more sustainable, cost-effective and high-performance products to the market,” says Ozcan. Cellulose nanomaterials manufactured in industrial quantities at relatively low cost will be an attractive option for many industries, including construction. For example, instead of having carpenters build specialized concrete molds, a company could 3D print them more quickly and more cost-effectively.

Biomaterials will be an important factor in a more sustainable composites industry. “In the past, we only looked at a material’s mechanical performance and its costs. Today, however, we also look at whether the feedstock is sustainable and renewable,” says Ozcan. “We are also looking at the life cycle assessment of the product. What can be done at end of life? How many times can it be used or recycled? What could be the next life for this material?” Discussing these issues at the design and manufacturing stages and making more sustainable choices will help keep composite materials out of landfills.

“People are waking up to the fact that we are consuming 1.75 planets a year in terms of the earth’s ability to renew resources,” says Forsyth. “We are going into a deficit with the planet.” Creative solutions are needed, and the composites industry needs to play a part in developing them.

SUBSCRIBE TO CM MAGAZINE

Composites Manufacturing Magazine is the official publication of the American Composites Manufacturers Association. Subscribe to get a free annual subscription to Composites Manufacturing Magazine and receive composites industry insights you can’t get anywhere else.